As a legal historian I thought I would share something this week from Penn’s collections that demonstrates both the frustrations and excitement of working with legal historical sources. A few weeks ago, the curator of manuscripts brought to my attention an uncataloged volume from the stacks which was known only to be some sort of “legal formulary” (now fully cataloged by Amey Hutchins as UPenn Ms. Codex 1628). Formularies, as their name suggests, are form books used by lawyers or others to record the particular language required for various legal proceedings. A formulary might then include forms for writing out deeds, conveying livestock, issuing a summons, etc. These might be taken from printed books of forms intended to guide lawyers or from manuscript documents used in actual practice and copied for later use [1]. From this description it’s easy to see why formularies don’t receive a lot of attention. They are often absurdly dull tomes full of a mishmash of legalese never meant to be read front to back but dipped into for templates by a practicing lawyer. I’m excited by nearly anything having to do with 18th century law but I have to admit having low expectations when I decided to investigate.

What I found instead was an ideal window onto the practice of law in the crucial  period between the end of British rule in Pennsylvania and the rise of the new United States.

period between the end of British rule in Pennsylvania and the rise of the new United States.

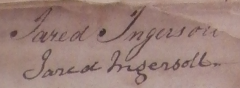

The very first page of the formulary (illustrated right) helped identify its owner and sometime author: Jared Ingersoll, Jr. (1749-1822). Ingersoll was one of the most prominent lawyers in the early American republic as well as a signer of the Constitution and later Attorney General of Pennsylvania. Originally from Connecticut, Ingersoll graduated from Yale and moved to Philadelphia around 1770 where he lived for the rest of his life except for 5 years in London (1773-78). Ms. Codex 1628 includes writing in several different hands but it seems more than likelythat the first 153 pages (all in the same hand) were written by Ingersoll himself as a young lawyer [2].

One doesn’t have to look much further than the opening page (above) to understand what kinds of material ended up in an early American form book. This first page contains a template to be used by the customs officer of Philadelphia for filing a bill to seize enslaved Africans brought to Pennsylvania without customs duties being paid. Note above the highlighted portions where particular names are omitted by Ingersoll for the template (e.g. “a certain ship called the ____”).

The appearance of documents like the one above raises a tricky question about what we can say based on a formulary. Does the presence of this form mean that young Philadelphia lawyers expected to deal with a number of slave-importation cases, or is it more emblematic of a desire to exhaustively document extant legal procedure no matter how common? In addition, while it seems reasonable to assume, given the presence of some specific dates in the form, that it was copied by Ingersoll from an actual bill filed for the seizure of enslaved persons, formularies also contain forms prepared for use but never actually used. The information contained within them then cannot always be taken at face value.

A more telling example of this problem comes on page 103 of the manuscript which contains a form for an “information” (similar to an indictment) for use by the “Negro Court” of Philadelphia. It may or may not record the details of an actual case before this specialized court. It includes placeholders for the names of the six white and property owning ‘jurors’ who were to try the case. The form does include specific language for a plausible crime, the theft of “one worsted pocket book” on the streets of Philadelphia, but includes Ingersoll’s note “here insert the Goods Stolen & their Value.”

However, historians can’t discount the evidence such a form presents. For instance, while we know that these courts were established by the Pennsylvania legislature in 1700 for the trial of all “Negro” offenders whether enslaved or free, historians have largely failed to find evidence relating to their actual practice or when they were convened [3]. Ingersoll’s copied form provides then one of perhaps the only windows onto the operation and persistence of these courts.

More interestingly, not all of the content copied into the formulary fits this template model. Ingersoll’s manuscript also includes full transcriptions of ephemeral documents that are not recorded in other surviving sources.

The document above comes from a period in the 1790s when Ingersoll was a practicing lawyer in front of the new U.S. Supreme Court in Philadelphia. This section of the manuscript includes several writs, orders, and other documents copied from Ingersoll’s day-to-day work at the Court. Entered into the formulary here is a 1793 notice seemingly sent from the Supreme Court notifying two parties in a case that the judgment in their favor by a Circuit Court in Pennsylvania (Livingston v. Swanwick) was being reviewed by the high court [4]. The early U.S. Supreme Court has been well-studied but to date no trace of the Court’s review of the Livingston case exists outside of this manuscript [5]. One reason for this omission is that the note above may not ever have been sent as we know that the Court did not end up hearing an appeal in Livingston’s case. Ingersoll perhaps had copied the draft letter before a decision on proceeding had been made. Note below the conclusion of the letter and the lack of a date or signature in the copy, details included in other Supreme Court documents copied in the volume.

This is all to say – manuscripts like Ingersoll’s formulary which appear dense, tedious, and of little value on the outside often bear dividends under closer examination.

*Update: 4 March 2013, a full facsimile of Ms. Codex 1628 is now available at Penn in Hand: http://dla.library.upenn.edu/dla/medren/detail.html?id=MEDREN_5839540 *

———–

[1] For more on early modern copying and legal practice see Harold Love, Scribal Publication in Seventeenth-Century England (Oxford, 1993) and Richard Ross, “The Memorial Culture of Early Modern English Lawyers: Memory as Keyword, Shelter, and Identity, 1560-1640,” Yale Journal of Law and the Humanities 10 (Summer 1998), pp. 229-326. There is also an accessible and decent wikipedia entry article on medieval and Roman formulary traditions.

[2]Dating the manuscript presents some difficulty, the latest date mentioned in the text is 1813 so it seems likely to have been discontinued after Ingersoll’s death. The first 106 pages consist of forms dating from the period of British colonial rule with no mentions of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. This might place the origins of the formulary in Ingersoll’s first period in Philadelphia (1770-3) but given the consistency in hand and Ingersoll’s tenure in England, it is also more than possible that he began the manuscript on his return in 1778. In addition, the volume, bought as a blank book is made up of paper bearing the watermark of the William and Levis papermill in Chester County, Pa. which operated 1775-1800. See Dard Hunter, Papermaking in pioneer America (Garland, 1981), p.158.

[3]This bill to establish “Negro courts” first passed the Pennsylvania legislature in 1700. These were abolished during the Revolution in 1780. See Gary B. Nash and Jean R. Soderlund, Freedom by Degrees: Emancipation in Pennsylvania and Its Aftermath (Oxford, 1991), p. 12.

[4] Livingston v. Swanwick as heard in April 1793 in the Pennsylvania circuit is reported at 2 U.S. 300 (1793).

[5] A team of legal historians spent several decades combing archives for papers relating to the U.S. Supreme Court prior to 1800. The results of this extraordinary research project were published in the 8 volume Documentary history of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1789-1800 (Columbia, 1985-2007). Also in UPenn Ms. Codex 1628 is a writ (pp.189-90) issued on 18 September 1792 by Justice James Wilson in the U.S. Supreme Court case Pagan v. Hooper that was not located by the editors of the Documentary History – see v. 6 p. 259.