In October 1796 Matthew Gregory Lewis, M.P., aged twenty-one, revealed himself to be the author of the recently published triple-decker The Monk and all hell broke loose.

Lewis had embraced the “Gothic imagination” popularized by Horace Walpole and Ann Radcliffe that “inspir[ed] terror and power … by creating sublime effects” (Groom 77). But instead of seeking “sublimity through mystification in order to probe the consequences of history and the telling of secrets” (Groom 79), Lewis penned a “violent, brutal, and sensational” tale that “revel[ed] in excess and corruption—the aesthetics of decay in its most lurid physical, moral, and social forms—and perpetually eroticize[d] his narrative with a perverse sexuality of voyeurism and role-play” (Groom 85). The titular monk, Ambrosio, is seduced by a witch masquerading as a fellow monk. He then becomes enamored of the innocent Antonia, whom the witch, Matilda, provides him the means to kidnap and rape. His first attempt goes awry, ending in his murder of Antonia’s mother Elvira; his second succeeds, but afterward he kills Antonia when she tries to flee. Taken by the Inquisition, Ambrosio sells his soul to the devil to escape prison, only to learn that Matilda is a demon sent to corrupt him, that Elvira was his mother and Antonia his sister, and that the devil, having released him from his cell, will take his price forthwith. And then there’s the side plot in which the unwilling nun Agnes, pregnant by her unsuitable suitor, is confined in a dungeon under the convent by her prioress …

The literary establishment averted its eyes and wrung its hands. “Situations of torment, and images of naked horror, are easily conceived,” tutted Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “and a writer in whose works they abound, deserves our gratitude almost equally with him who should drag us by way of sport through a military hospital, or force us to sit at the dissecting-table of a natural philosopher” ([web]). “A legislator in our own parliament, a member of the House of Commons of Great Britain, an elected guardian and defender of the laws, the religion, and the good manners of the country,” thundered Thomas James Mathias, “has neither scrupled nor blushed to depict and to publish to the world the arts of lewd and systematic seduction, and to thrust upon the nation the most open and unqualified blasphemy against the very code and volume of our religion” (ii-iii). The reading public, on the other hand, was all agog: “They had been told that the book was horrible, blasphemous, and lewd, and they rushed to put their morality to the test. By 1800 five London and two Dublin editions, to say nothing of pirated versions and abridgments, were needed to supply the market” (Peck 28).

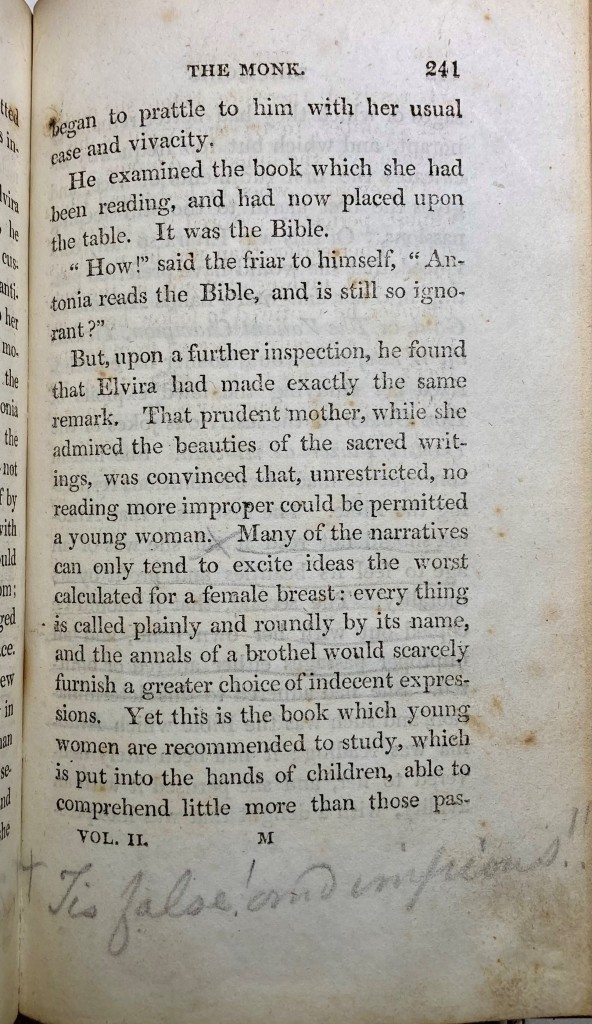

Often singled out for the charge of blasphemy was a passage in chapter 7 of the second volume in which Ambrosio wonders how “Antonia reads the Bible, and is still so ignorant [of sexual matters]” (II, 241). What follows is a satirical description of Christianity’s Scriptures as “tend[ing] to excite ideas the worst calculated for a female breast:

every thing is called plainly and roundly by its name, and the annals of a brothel would scarcely furnish a greater choice of indecent expressions. Yet this is the book which young women are recommended to study, which is put into the hands of children, able to comprehend little more than those passages of which they had better remain ignorant, and which but too frequently inculcates the first rudiments of vice, and gives the first alarm to the still-sleeping passions. (II, 241-242)

To his surprise, the lustful Ambrosio finds himself in agreement with Antonia’s “prudent mother” Elvira who “was convinced that, unrestricted, no reading more improper could be permitted a young woman” (II, 241). Antonia’s Bible has been “copied out by [Elvira’s] own hand, and all improper passages either altered or omitted” (II, 242).

For some readers, this perspective had the merit of acknowledging that not every episode in the Bible is rated E for Everyone (or in patriarchal terms, G for Girls). “The indiscriminate perusal of such passages as occur, in which every thing is called by its vulgar name, in which the most luxuriant images are described, as in Solomon’s Song, must certainly be improper for young females,” opined an anonymous reviewer. “So fully aware were the Jews of this truth, that they prohibited the reading of Solomon’s Song, till a certain age, when the passions are in subjection” (quoted in Macdonald 131). For others, like Mathias, Lewis’s puerile flippancy was beyond the pale. “I believe this 7th Chap. of Vol. 2 is actionable at Common Law,” he warned, adding, “The falsehood of this passage is not more gross than its impiety” (Mathias ii, iii). Lewis and his publisher Joseph Bell seem to have avoided prosecution: the author’s obituary, published two decades later, states that “on a pledge to recall the copies, and to recast the work in another edition, legal proceedings were stopped” (quoted in Parreaux 114). That edition, titled Ambrosio, or, The Monk (London: Bell, 1798), was as thoroughly bowdlerized as Antonia’s Bible: “[Lewis] not only softened down ‘ravisher’ to ‘intruder,’ ‘incontinence’ to ‘weakness,’ ‘lust’ to ‘desire,’ and ‘desires’ to ’emotions,’ but entirely left out several passages, including the one on the Bible” (Macdonald 134). But Bell, rather than pulp the unexpurgated volumes, raised their price and coyly advertised, “A few remaining copies of the original edition may be had by applying to the Publisher” (quoted in Macdonald 135).

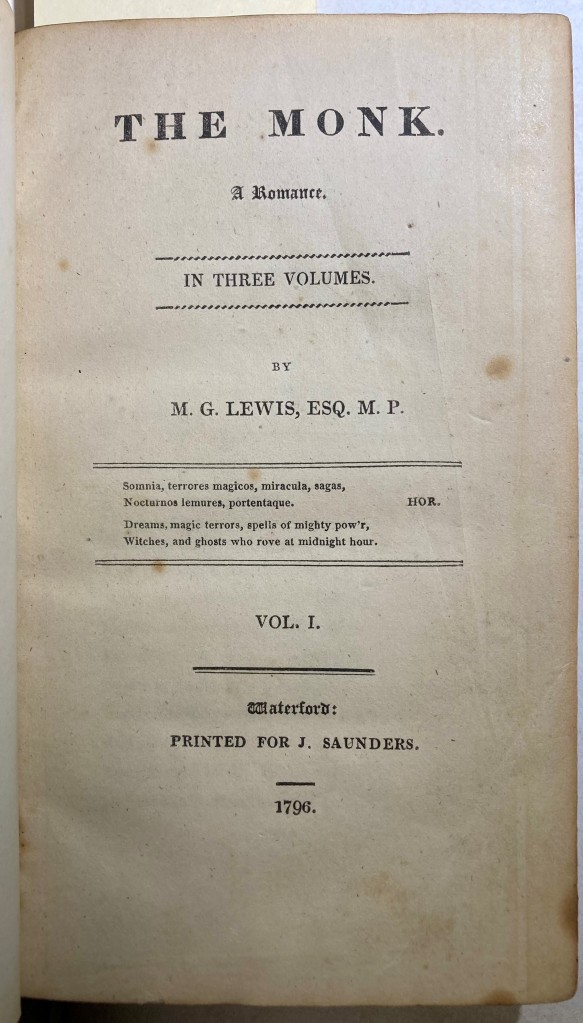

The appetite for Lewis’s novel in its original perverse glory remained undiminished, which brings me to a Kislak Center copy of The Monk, ostensibly printed in Waterford, Ireland, for J. Saunders in 1796 (see its title leaves, pictured above), but actually a probable London publication on paper watermarked 1818 (ESTC T169350). These three volumes replicate the text of Bell’s second edition of October 1796 (Todd 22), retaining what Lewis subsequently deleted. And among all those restored passages, only one has sufficiently drawn the ire of a reader to record his or her opinion: volume 2, chapter 7, pages 241-242, concerning the indecency of the Bible.

On page 241 the sentence beginning “Many of the narratives can only tend to excite ideas the worst calculated for a female breast …” has been underlined and footnoted: “Tis false! and impious!!” On page 242 the first four lines (“… of which they had better remain ignorant, and which but too frequently inculcates the first rudiments of vice, and gives the first alarm to the still-sleeping passions.”) are similarly underlined and even more emphatically footnoted: “False! False!! As Hell!!!” To this reader, as to Lewis’s contemporary critics, “the Bible was not just a book like others, not even a very great book,” as André Parreaux writes. “They would have been horrified at the idea that the Bible could be, as modern editors say, ‘read as literature’. It was the Word of God, and, as such, the basis of all Christian faith and teaching” (98). The idea that God, speaking through the Bible, “inculcates the first rudiments of vice” is quite literally anathema to the devout.

Buoyed by youthful self-confidence, Lewis seems not to have expected the antipathy expressed toward his audacious book. “I am so pleased with it,” he told his mother when he had a finished draft in hand, “that, if the Booksellers will not buy it, I shall publish it myself” (quoted in Peck 19). His anticipation of success was not unwarranted: the bestseller lists of the turn of the nineteenth century included both Gothic novels like Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho, which “[went] through ten editions in its first decade, including those published in Dublin, Boston and Philadelphia” (Ellis 51) and “literary erotic productions like The Poetical Works of the Late Thomas Little, Esq., [by Thomas Moore] which ran to eleven editions between 1801 and 1813″ (Parreaux 96). Such works, however, were addressed to and consumed by very different audiences. Wardman Ellis suggests that hostile reactions to The Monk spotlight the combination of its popular literary mode with its niche licentious matter: “The libertine sections (sexual and blasphemous) were little more than conventional for an under-the-counter publication for gentlemen’s interest only … [B]ut in the form of the novel, especially in its sensationalist gothic mode, such libertine discourse was scandalous, because it addressed a wide and indiscriminate audience, including many young women” (115).

In the end, the embattled author acceded to public pressure and redacted the worst of his solecisms. Three years later, however, like many a twenty-first-century twenty-something whose notoriety stems from a high-profile gaffe, “Monk” Lewis professed himself sorry that anyone had been offended. “A fault, were it one ever so serious, committed at twenty, and followed during a course of years by no error of a similar nature, might, I should think, be forgiven without exercising any dangerous lenity, or requiring any very great exertion of candor,” he wrote in the preface to his drama Adelmorn the Outlaw, published in 1801.

That I have not found such candor, however, I do not very poignantly regret: what pains but little, is not worthy a complaint, and censure is only terrible to me when I feel it to have been merited … Hitherto I have only listened with contempt to censure inflicted without justice; for once, and for once only I will alter my conduct, and address a few words on this head to those who may feel any interest respecting me.

Without entering into the discussion, whether the principles inculcated in The Monk are right or wrong, or whether the means by which the story is conducted is likely to do more mischief than the tendency is likely to produce good, I solemnly declare, that when I published the work I had no idea that its publication could be prejudicial; if I was wrong, the error proceeded from my judgment not from my intention.

Without entering into the merits of the advice which it proposes to convey, or attempting to defend (what I now condemn myself) the language and manner in which that advice was delivered, I solemnly declare, that in writing the passage which regards the Bible (consisting of a single page, and the only passage which I ever wrote on the subject) I had not the most distant intention to bring the sacred Writings into contempt, and that, had I suspected it of producing such an effect, I should not have written the paragraph. (Lewis v-vi; emphasis in original)

Works Cited

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. “Review of Lewis’s The Monk (1797).” Kathy Larsen, George Washington University, 16 May 2024, home.gwu.edu/~klarsen/review.html.

Ellis, Markman. The History of Gothic Fiction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2000.

Groom, Nick. The Gothic: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Lewis, M. G. Adelmorn the Outlaw. London: J. Bell, 1801.

Macdonald, D. L. Monk Lewis: A Critical Biography. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000.

Mathias, Thomas James. The Pursuits of Literature. Part 4. London: T. Becket, 1797.

Parreaux, André. The Publication of The Monk: A Literary Event 1796-1798. Paris: Marcel Didier, 1960.

Peck, Louis F. A Life of Matthew G. Lewis. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1961.

Todd, William B. “The Early Editions and Issues of ‘The Monk’”‘ With a Bibliography.” Studies in Bibliography 2 (1949/1950): 3-24.