-

They grow up so fast: Getting to know Sarah Wistar Pennock through her childhood letters

My favorite items from the Wistar, Pennock, Lukens, Miller, and Davis family papers are Sarah Wistar Pennock’s (1840-1909) letters that she wrote between the ages of six and thirteen. I believe that I’m drawn to her correspondence specifically because of my nearly ten years of experience as a high school teacher. Adolescents experience a lot…

-

“Books Are a Symbol of Liberty”

Previously on Paeans to Books on Dust Jackets, we had the argument that “[a] book is best! absolutely!” from the first American edition of The Voice of the Crab (New York: Harper and Row, 1974) by Charlotte Jay. Today we are urged to consider that “[b]ooks are a symbol of liberty” by American children’s book…

-

The Kislak Kitchen: Eliza Pierce’s Clove Cake

The Eliza Dwight Pierce cookbook came to the Kislak Center via the Nick Malgieri Culinary Archive and Library as the Mrs. John J. Pierce cookbook. Its original title demonstrates a common problem in archival work: a woman identified only by her husband’s name. Per usual, I felt determined to give her back her name, which…

-

It Takes a Lot of Power to Play Lightning and Thunder

I’m old enough to remember shopping for music in physical stores, flipping through the albums by hand in the hopes of finding a hidden gem. Sometimes I’d take a chance buying an album based entirely on the intriguing artwork on the cover, but this was an unreliable way to spend my money. I recently had…

-

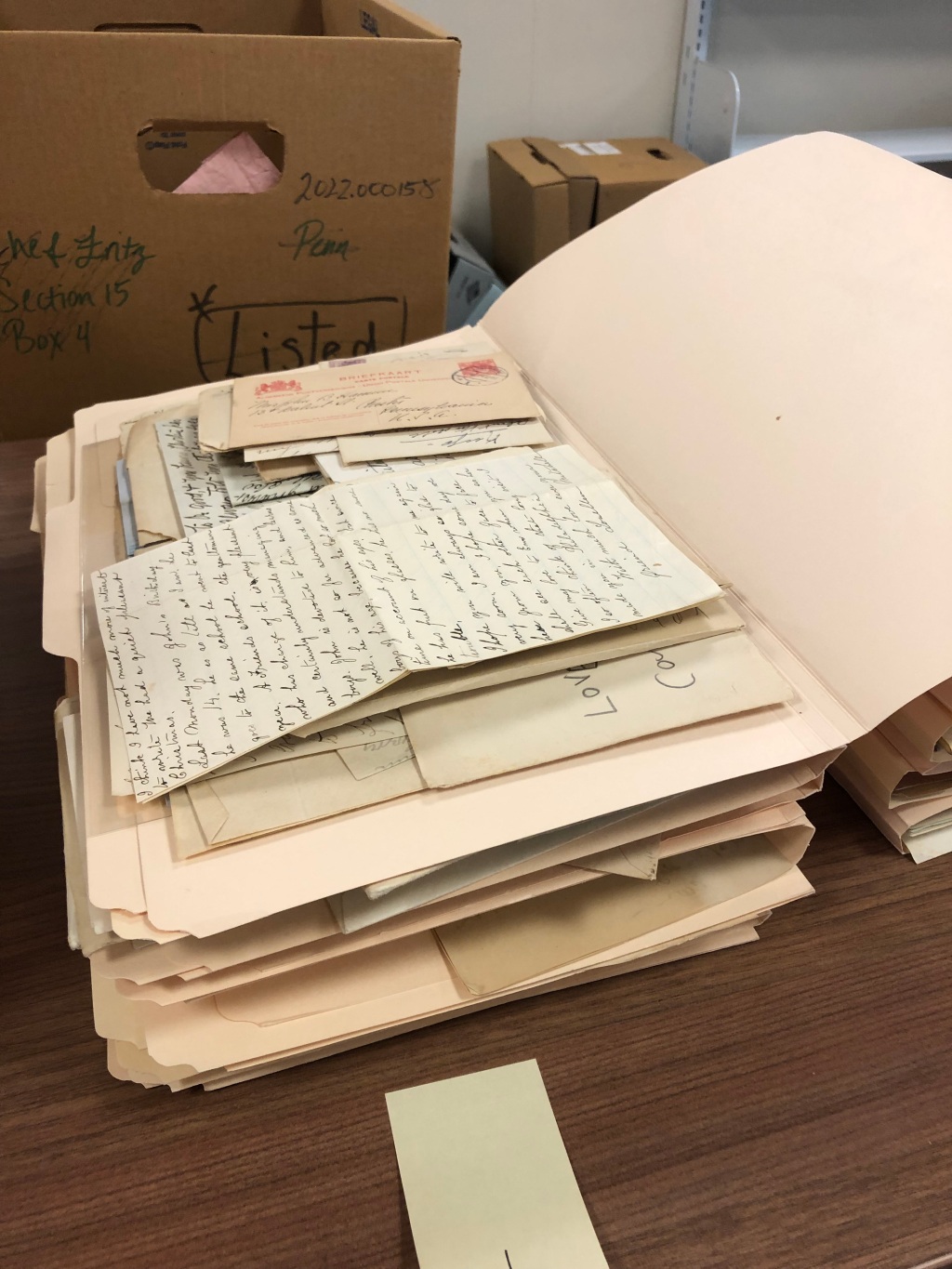

Loose Lips Sink Ships

For men and women deployed during World War II, mail was an important morale boost. Letters from home were a brief escape from the stress and dangers military and civilian personnel experienced daily. The Ann Ingersoll Townsend Simpson papers are full of correspondence to and from her while she was serving in the China Burma…

-

The Philadelphia Orchestra, an Argentinian researcher, and the Free Library of Philadelphia

STORIES FROM THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA ASSOCIATION RECORDS In honor of National Library Week, I’m sharing a story of The Philadelphia Orchestra, a scholar from Argentina, and the Free Library of Philadelphia. While processing the files of the Orchestra’s administrative staff, I came across a letter written in Spanish, addressed to the “Orquesta Sinfonica Filadelfia, U.…