[Ed. Note: Today’s post comes from Mike Williams, a Japanese Specialist here at the Penn Libraries]

[Auth. Note: Due to bibliographic evidence and mild demand of researchers and interested parties, I have adjusted the romanization of the title from Tachikawa to Tatsukawa. Updated July 22, 2013.]

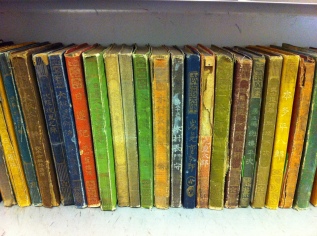

For many years, a faded assortment of colorfully-bound but unassuming Japanese books sat relatively undisturbed in the East Asia stacks, perhaps examined once or twice, but almost never circulating. These items—small, aging, and brittle—were retired from active browsing and sent to the Penn Libraries’ High Density Storage facility (now LIBRA).

The Libraries’ bibliographic records for these books were mostly bare-bones: brief catalog cards bearing limited romanized information with additional material in Japanese were soon replaced by digital records—with all of the valuable “vernacular” script stripped out. Now buried even deeper than before in storage, this treasury of early 20th century fiction lay in wait for someone to dig them up again.

So dig I did. Armed with a stack of original cards from the East Asia card catalog and data freshly harvested from the Libraries’ Data Farm, I was able to get all of the books unearthed and shipped right to me. These diamonds-in-the-rough—or perhaps, roughly-hewn gemstones, given their panoply of colors and well-worn condition—proved to be much more interesting than I had imagined.

Scope of the Collection

The collection of early Taishō period (more properly, very late Meiji through early Taishō) fiction held at the Libraries is a snapshot of early 20th century Japanese publishing history. These 188 small books (roughly 12.75 cm high by 9.25 cm wide) largely contain tales of bravery and adventure: reimagined samurai swashbucklers, ninja-turned-heroes, fantastic journeys, and wars of glory. The romanticized bygone days of the post-medieval Edo period (1600-1868) provided a wealth of material for young urban readers.

Only two of these volumes stand alone as “single works”—the remaining 186 were all issued as volumes in a series (generally numbered). The Penn Libraries’ holdings of these pocket books span a few series, none of which are completely owned. The majority of these books feature a series bibliography in the form of publisher’s advertisements (found after the colophon page, generally located at the end of Japanese books). Whether or not these had been published or merely planned is not clear. Even Nichigai Associates, an information specialist company whose bibliographies are enormously helpful in identifying Japanese materials in print, draws complete blanks on some of the titles Penn holds. Of the ten series represented in the collection, Nichigai’s “Catalog of Series in Japan 1868-1944” lists only four—and none of these are without incomplete portions. In fact, some of these series and titles are truly unique at Penn, with no records of them in libraries or used book networks worldwide. With scant publication records in existence, the best source of describing what may have existed is the items themselves—many of which, of course, no longer exist.

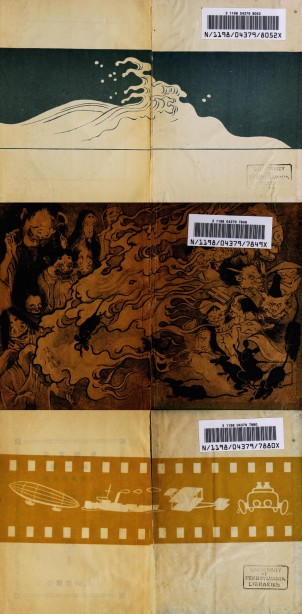

While the Penn Libraries is still in the process of enriching our catalog with careful description and Japanese scripts, the following series bibliography with the number of volumes owned of each can be offered: Bushidō bunko [武士道文庫] (3 titles) ; Katsudō bunko [活動文庫] (2 titles) ; Kaiketsu bunko [怪傑文庫] (2 titles) ; Kodan bunko [講談文庫] (3 titles) ; Okamura kōdan sōsho [岡村講談叢書] (6 titles) ; Shidan bunko [史談文庫] (30 titles) ; Shūchin bunko [袖珍文庫] (10 titles) ; Shūchin Okawa bunko (AKA Shūchin shosetsu bunko) [袖珍大川文庫・袖珍小説文庫] (61 titles) ; Tatsukawa bunko [立川文庫] (61 titles) ; Taishō bunko [大正文庫] (8 titles).

Of these, the focus of much scholarly research and nostalgic reminiscences has been the Tatsukawa bunko series.

Tatsukawa Bunko: Popular Fiction and the Birth of the Heroic Ninja

The stories that formed Tatsukawa bunko and enthralled their readership trace their origins back to the spoken-word performance art of kōdan in the latter half of the 20th century. Kōdan featured stories of heroism and wars, delivered in a dramatic and colloquial but certainly professional style. These tales eventually formed the basis for a genre of literature called sokkibon, or to use J. Scott Miller’s term, “phonobooks”. Stenographers of kōdan used newly-imported Western techniques for shorthand (sokki) to transcribe the narratives of performers into readable texts. These printed stories, written with a decidedly oratory style, proved to be hugely successful in the greater Osaka area. With the proliferation of sokkibon as a literary genre, authors familiar with the kōdan and sokkibon penned their own stories in the same vein, conflating the functions of both storyteller and transcriber.

It was from the minds of professional storyteller Tamada Gyokushūsai (1856-1921) and his second family that the wildly popular stories of Tatsukawa bunko were conceived. Born Katō Manjirō, Tamada trained as a tale-teller under the first Gyokushūsai, who specialized in Shinto religious tales. After Gyokushūsai’s death, Katō assumed the mantle of his former mentor. Tamada’s first wife and child died of cholera, but later he became acquainted with a woman named Yamada Kei (1855-1921). Kei, already a married woman, ran off with Tamada and brought her children with her, eventually settling in Osaka.

Tamada, his wife, and his stepchildren (in particular eldest son Otetsu) collaborated on creating stories for publication. Eventually, the idea of a serialized sokkibon publication occurred to the family, who shopped around the idea with little success. Finally, the proprietor of publishing house Tatsukawa Bunmeidō, Tatsukawa Kumajirō (1878-1932) received their idea with enthusiasm and began publishing their stories under the name Tatsukawa bunko, which has often been referred to with colloquial pronunciation Tachikawa bunko (a trend that library catalogers have followed).

The books were marketed chiefly to a juvenile audience, mostly the poor teenage apprentices of the Osaka area. Designed to fit easily into the pockets of these working youth, the Tatsukawa bunko volumes priced between 25-30 sen (a now obsolete unit valued at 1/100 yen). Although poor apprentices could not afford to spend all of their pocket money on reading material, Tatsukawa Bunmeidō offered a novel trade-in deal: a new volume could be purchased by trading in an older volume, with an additional 3 sen trade-in fee. Of course, readers borrowed and lent titles amongst their friends as well.

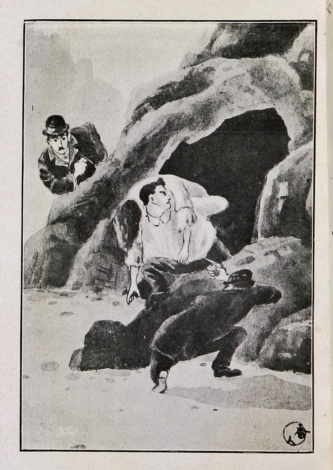

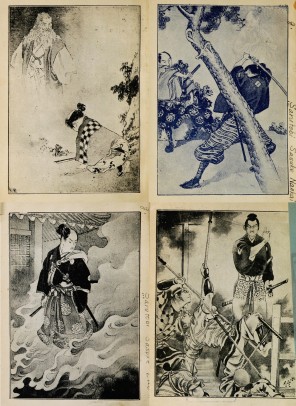

Between 1911 and the mid-1920s, roughly 200 titles were produced to meet the rampant demand (the exact number of books is uncertain—see the Notable bibliographies of Tatsukawa bunko at the end). The content of these books were largely jidai shōsetsu, or historical fiction. But the character that provide to be the breakout success of the Tamada-Yamada creative team was ninja Sarutobi Sasuke, or “Monkey-Jump Sasuke”, who debuted in 1913 in volume 40 of Tatsukawa bunko (Penn owns a 1916 edition, and a reproduction of a 1914 edition). A fusion of historical and fictional accounts of ninja with the skills of legendary literary hero Sun Wukong (known in Japanese as Son Gokū), Sarutobi Sasuke was a new type of ninja, largely unfamiliar to his readership. Rather than serve as a villain corrupted by the dark arts of ninjutsu, Sasuke was a spritely and mischievous antihero who used his myriad magic powers for virtuous ends. Sasuke continued to appear in other Tatsukawa titles, and his popularity heralded the rise of a “ninja boom” that lasted until the latter 1920s.

With the death of Tamada in 1921, the Yamada family’s literary efforts waned. Tatsukawa Bunmeidō continued to operate and reprint earlier titles of the series, up until the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake. Tatsukawa Bunmeidō continued to publish until early 1945, when an air raid on Osaka destroyed their offices, records, and all of the printing plates within.

Tatsukawa Bunko in Comparison

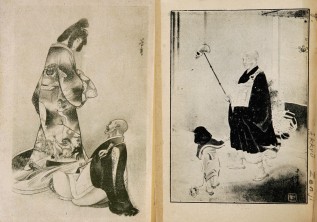

Each volume of Tatsukawa bunko was bound in cloth in one of seven colors (red, blue, yellow, green, orange, black, or purple) with spines featuring the full title in gold leaf. Almost every book featured a frontispiece by ukiyoe artist Hasegawa Sadanobu III (1881-1963). These artistic merits surely appealed to their readership and lent an air of literary legitimacy to these cheaply produced books.

As the forerunner of the “bunko boom”, Tatsukawa bunko became something of a household name. Imitators of Tatsukawa’s success such as Taishō bunko and Shidan bunko (both held in part by the Penn Libraries) sold well, but continued to be compared to and grouped under the generic trademark of Tatsukawa bunko. Many competing series, many published in Osaka and others in Tokyo, modeled their look on the Tatsukawa books. Bound in bright colors, given elaborate spine designs, and some featuring their own frontispieces, these books are on first glance indistinguishable from Tatsukawa bunko volumes. Indeed, seeing all of these volumes together in bulk, I had thought they had all been published by the same company. Take a look at the photo from earlier on: the Tatsukawa books each have a five-petaled flower on the lower half of the spine; the other books are all from competitors.

While Tatsukawa bunko and other Osaka-based bunko sets focused largely on historical fiction and fictional historical personages like Sarutobi Sasuke, Tokyo publishers drew on the wealth of existing national literature. Shūchin bunko, for instance, reprinted many classics of Japanese literature, from the 8th century Kojiki to Edo period novels. The similarly named but distinct Shūchin Ōkawa bunko took a more middle-road approach, publishing biographical fiction of well-known warriors along with classical war stories like Genpei seisuiki and the Edo samurai tale Nansō Satomi Hakkenden.

The Tokyo-Osaka/East-West divide can be further noted in that the exploits of the Tokugawa clan, the family who held the shogunate of Japan during the Edo period, are treated with very different tones depending on the locality. Osaka area bunko stories painted the Tokugawas, particularly Ieyasu, as villains to be thwarted, while Tokyo-based bunko featured them as heroes. These conceptual differences notwithstanding, competing publishers did feature some of the same notable personages, whose exploits were unaligned with regional sentiments.

Many more pocket fiction titles similar to Tatsukawa bunko existed as well. An exhibition held at the Himeji Bungakukan in 2004 featured representative volumes of at least 18 other series. One of these titles, Poketto sōsho, measures roughly two times smaller than Tatsukawa bunko, at a diminutive 9 cm high by 6.5 cm wide. See the exhibition catalog Tatsukawa Kumajirō to Tatsukawa Bunko: Taishō no bunkoō for details.

The Future of the Collection

Some of these materials may not exist anywhere else in the world, and are extremely unlikely to be reprinted. Although some reproductions of Tatsukawa materials exist, these are largely out of print as well, and do not offer a complete reproduction of the series as a whole. As the Penn Libraries embark on a reevaluation of the bibliographic description for these precious items, some of which Penn uniquely holds, we are exploring options for the preservation and access to their content.

Collection Update (October 29, 2014)

The entire collection described in this post has been digitized and is now available through Print at Penn as the Japanese Juvenile Fiction Collection. The number of physical volumes (188) is greater than the amount of digitized titles, since some are multivolume sets represented by one digital facsimile. The print collection has also expanded by several newly purchased titles, and new digital facsimiles may be added in the future. For digitized materials only, the option to narrow results by titles with facsimiles (Facsimile = “Yes”) may be selected.

I would like to thank: Joe Kishman and the staff of LIBRA for kindly and carefully shipping these fragile materials to me; PJ Smalley for scanning help; and all the ILL staff who helped me procure articles and books for my research.

For further reading and bibliographical information about Tatsukawa bunko…

Notable bibliographies of Tatsukawa bunko

Given that each volume of Tatsukawa bunko bears a listing of the cumulative series contents, building a bibliography of the series seems simple enough. This is not the case. For example, the post-colophon series listing of volume 108 (a Sarutobi story) lists volume 108 as Kumada Jingobē (which was actually published as volume 105). Moreover, the final page of this Sarutobi tale ends with an illustrated announcement of the next installment of the series Bonji Tarō, which the reader may guess as volume 109. Instead, this title appeared in print as volume 111, despite being listed as volume 106 in the volume-end series bibliography. Despite these difficulties, several notable bibliographies have been constructed.

- Himeji Bungakukan [姬路文学館]. Tatsukawa bunko kankō ichiran [立川文庫刊行一覧]. In Tatsukawa Kumajirō to Tatsukawa Bunko: Taishō no bunkoō [立川熊次郎と「立川文庫」—大正の文庫王]. (Himeji: Himeji Bungakukan, 2004).

Complete with listings up to vol.201 (some volumes listed as “unknown”), this bibliography refers to earlier bibliographies and also provides notations on what intuitions and individuals own each volume. Some volumes are not listed as owned by anyone. Of these, Penn holds seven titles (vols. 24, 68, 90, 92, 96, 104, and 114).

- Imabari Shiritsu Toshokan [今治市立図書館]. Tatsukawa bunko shozō ichiran [立川文庫所蔵一覧].

This incomplete bibliography spans from vol.1 to vol.197, offering the holdings of the Imabari City Library, in Ehime Prefecture, Japan, where Tatsukawa bunko is kept as a special collection. The Sarutobi titles are in blue, with a ninja graphic nearby. Accessed Apr. 12, 2013.

- Kyokudō, Nanryō [旭堂南陵]. Zokuzoku, Meijiki Ōsaka no engei sokkibon kiso kenkyū [続々・明治期大阪の演芸速記本基礎研究]. Osaka: Taru Shuppan, 2011.

The most recent comprehensive bibliography provides detailed information on extant printings/editions, including variant statements of responsibility and pagination differences amongst comparative copies of the same volume title. Vol. 1, Shokoku man’yū Ikkyū zenji, for instance, ranges from a 219 page “2nd” edition published in 1911, to a 319 page “27th” edition published in 1914. Interestingly, a “9th” edition from 1920 measures at 282 pages. Such discrepancies seem to have evened out as the series progressed.

- Niijima, Kōichirō [新島廣一郎]. “Shōnen kōdanshū” shiryō: “Tatsukawa bunko” mokuroku [「少年講談集」資料―「立川文庫」目録]. In Shōnen shōsetsu taikei, bekkan 2 “Shōnen kōdanshū” (Tokyo: San’ichi Shobō, 1995).

Fairly complete with listings up to vol.201 (some volumes missing), this bibliography draws from Niijima’s own collection as well as others’, and revises the bibliography from the first edition of Adachi Ken’ichi’s Tatsukawa bunko no eiyūtachi (Tokyo: Bunwa Shobō, 1980). This bibliography clearly delineates the titles from their tsunogaki, or “supratitles”.

- Nichigai Asoshiētsu [日外アソシエーツ]. Zenshū, sōsho sōmokuroku: Meiji, Taishō, Shōwa senzenki II: Kagaku, gijutsu, sangyō, geijutsu, gengo, bungaku [全集・叢書総目録:明治・大正・昭和戦前期Ⅱ 科学・技術・産業・芸術・言語・文学]. Tokyo : Nichigai Asoshiētsu, 2007 (p.1120-1123).

This title listing ends at vol.186 and does not offer the explanatory tsunogaki. It does document the printings consulted (one title was printed at least 20 times). Curiously, some volume numbers are duplicated with variant titles, or completely different titles altogether.

References for Further Reading

- Adachi, Ken’ichi [足立巻一]. Tatsukawa bunko no eiyūtachi [立川文庫の英雄たち]. Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha, 1987.

- Himeji Bungakukan [姬路文学館]. Tatsukawa Kumajirō to Tatsukawa bunko: Taishō no bunkoō [立川熊次郎と「立川文庫」—大正の文庫王]. Himeji: Himeji Bungakukan, 2004.

- Imabari Shiritsu Toshokan [今治市立図書館]. Tatsukawa bunko shozō ichiran [立川文庫所蔵一覧] (Updated link Oct. 29, 2014)

- Kuwabara, Saburō [桑原三郎]. Tatsukawa bunko to shōnen kōdan no bōkendan no shudai: “Miyamoto Musashi” ron [立川文庫と少年講談の冒險譚の主題—「宮本武藏」論]. Kokubungaku kaishaku to kyōzai no kenkyū, vol.32 no.12 (Oct. 1987).

- Kyokudō, Nanryō [旭堂南陵]. Meijiki Ōsaka no engei sokkibon kiso kenkyū [明治期大阪の演芸速記本基礎研究] (series). Osaka: Taru Shuppan, 1994-present.

- Kyokudō, Nanryō [旭堂南陵]. Meijimatsu—Taishōki Ōsaka kōdanbon no sekai: Tatsukawa bunko o chūshin ni [明治末〜大正期大阪講談本の世界―立川文庫を中心に]. Ōsaka no rekishi, vol.66 (July 2005).

- Langton, Scott Charles. A literature for the people: a study of the jidai shosetsu in Taisho and early Showa Japan. Dissertation for The Ohio State University, 2000.

- Miller, J. Scott. Japanese shorthand and sokkibon. Monumenta Nipponica, vol.49, no.4 (Winter 1994).

- Niijima, Kōichirō [新島廣一郎]. Shōnen oigataku [少年老い難く]. Shōnen shōsetsu taikei geppō, no.25, Mar. 1995. Issued with Shōnen shōsetsu taikei, bekkan 2 “Shōnen kōdanshū” (Tokyo: San’ichi Shobō, 1995).

- Ozaki, Hotsuki [尾崎秀樹]. Kaisetsu [解説]. In Shōnen shōsetsu taikei, bekkan 2 “Shōnen kōdanshū” (Tokyo: San’ichi Shobō, 1995).

- Ozaki, Hotsuki [尾崎秀樹]. Taishū bungaku no rekishi, jō: Senzen hen [大衆文学の歴史 上: 戦前篇]. Tokyo : Kōdansha, 1989.

- Torrance, Richard. Literacy and literature in Osaka, 1890-1940. Journal of Japanese Studies, vol.31, no.1 (Winter 2005).

10 responses to “Early Taishō Japanese Juvenile Pocket Fiction: Tatsukawa Bunko and its Imitators”

Thank you so much for this very interesting essay, which inspired me to dig in. FYI, Japan’s National Diet Library (NDL) database brought some 230 bib records for Tachikawa bunko published between 1900-1926. 83 of NDL’s holdings are fully digitized and most of them are freely accessible. Quality of images are not great though. eg. http://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/904207

Kuniko, thanks for your comment and your insightful digging around.

Indeed, NDL does return many hits on “Tachikawa bunko”. I see 128 results for “books” with the date range of 1900-1930 and limited to NDL-held volumes only. 17 of these are further genred as “children’s books”. Some of these images are indeed of better quality than others, though all of them are greyscale. Interestingly, not all of the NDL records bear the series enumeration. Perhaps some items are missing their covers, which are the best source of this often elusive number.

Nevertheless, NDL’s rich data and digital surrogates would certainly help researchers document the histories of Tachikawa’s publications. The colophons of Tachikawa books do not trace the various editions and printings: in fact, each volume would appear to be a “first edition”. Lacking this vital “版” information, one might likely require comparative colophons to chase down first editions.

I hope that Penn’s collections will provide one of many avenues of study for scholars of early 20th century fiction and publishing history in Japan.

Fascinating article, thanks for taking the time to share!

This article was fascinating! Having read it, i find myself wanting to know more especially the artwork.

Fascinating! Did you also find examples of early Japanese science fiction, and if so, could you please tell me more?

Best regards,

Theo Paijmans

Theo, we did not find any clear examples of early science fiction in our collections.

Japanese “science fiction” may have existed as far back as the Heian period (794-1185), though the type of sci-fi that 21st century people may imagine might have begun more properly with the works of authors like Oshikawa Shunrō and Unno Jūza. Oshikawa died during the golden age of these bunko books, and his noted book Kaitei Gunkan (“Submarine Warship”, detailed on his page linked above) seems to have first been published in 1900, perhaps as a very early forerunner of these bunko books. Unno began writing about a decade after these bunko were published. Unno’s works do not seem to have been translated into English as of this reply, though Oshikawa’s Kaitei Gunkan was somewhat adapted into an anime, Super Atragon.

[…] of this blog may remember, The Penn Libraries’ Japanese Studies unit has enjoyed rediscovering unique snapshots of Japanese bibliographic history. But this most recent find came from an unexpected place: Penn’s Evans Bible Collection. […]

[…] of many of these in the US, and some in the world. Please see Japanese/Korean library specialist Mike Williams’s Unique at Penn post about the collection for more […]

[…] of the works are from such famous series as the Tatsukawa (Tachikawa) Bunko series. As described in this article on the collection by Mike Williams, a specialist at the UPenn […]

[…] names. These books are so similar in size, design, and layout they they are near-fungible. Like the many imitators of the famous Tachikawa Bunko in our juvenile fiction collection, here we see books camouflaging themselves as each other. But […]