[Ed. Note. Today’s post comes from Dr. Elisabeth Esser Braun, the donor of the book discussed here. She was born in Cologne, Germany, completed her undergraduate education in Europe, and earned a doctorate from the Patterson School of Diplomacy and International Commerce at the University of Kentucky. She worked as a journalist at the United Nations and as an international executive. She retired in 1990 and now lives in Haverford, Pa.]

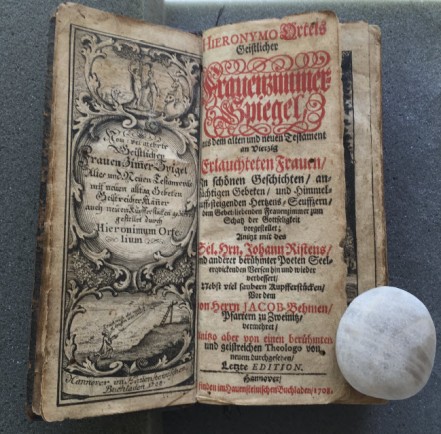

I recently came across a box of family memorabilia that included Hieronymus Oertl’s Geistlicher Frauenzimmerspiegel, published in Hanover, Germany, in 1708.

I was intrigued and wanted to know: What is a Frauenzimmer-spiegel? Who was Hieronymus Oertl? Why and for whom was this book written? How many copies exist?

Researching the story of the Geistlicher Frauenzimmerspiegel has been an interesting quest. Scant literature on the subject exists, either in German or in English [1]. However, we know from secondary sources that this was the time of popular piety (Volksfroemmigkeit) and that these books were written as devotional and edifying guides (Erbauungsliteratur) for a female readership. Similar to Catholic prayer books and stories about the lives of saints, these books were meant to encourage Protestant women (Frauenzimmer) to lead virtuous lives as mirrored (Spiegel) in the lives of Biblical women of the Old and New Testament. The text was compiled from many sources and the books were lavishly illustrated with copperplate engravings so as to appeal through image as well as text.

The virtues highlighted in the Frauenzimmerspiegel were wide ranging. They focused on a woman’s role as wife and mother in a patriarchal society and included, among others, honesty, chastity, obedience, wisdom, courage and, more generally, strength through prayer. Even if a woman failed to conduct herself properly, all was not lost since God, in his infinite wisdom, always granted redemption through penitence and prayer. These virtues reinforced the patriarchal hierarchy of society and validated God’s orderly plan for his creation of life on earth.

Among the forty exemplary biblical women included in the Frauenzimmerspiegel were Eve, the mother of all living beings; Sara, the blessed one; Hagar, the exiled one; Lea, the patient one; Debora, the courageous one; Rahab, the faithful one; Abigail, the reasonable one; Esther, the devout one; Susanna, the chaste one; and Maria Magdalena, the repentant one.

Hieronymus Oertl, the author of the Geistlicher Frauenzimmer-spiegel, was no amateur scribe. He was born in the Free Imperial City of Augsburg and died in the Free Imperial City of Nuremberg. Although disputed, most German sources identify the year of his birth as 1543 and that of his death as 1614.

The Oertl family was well established in Augsburg. They were merchants and also served as professional bureaucrats in the administrations of four Habsburg Emperors: Charles V (resigned in 1556), Ferdinand I (d.1564), Maximilian II (d.1567) and Rudolph II (d.1612). The Oertls were quiet Protestants and had been so long before the Peace of Augsburg (1550) that concluded the era of religious strife in Germany and recognized the right of territorial princes to determine the religion of their subjects. This was popularly interpreted as promoting equal rights for Catholics and Protestants in the Imperial realm.

Little is known about Hieronymus’ education. He joined the Imperial household at age 15 and advanced from Schreibmeister (writing master), copying calligraphic manuscripts, to chronicler, author, and notary. Oertl’s name emerged from obscurity in 1578, when a group of Protestants in Vienna presented a petition (Bittschrift) to the unyieldingly Catholic Emperor Rudolf II asking that Catholics and Protestants be assured equal religious freedoms in Austrian territories, as had been sanctioned in the Peace of Augsburg in 1550.

The petition was summarily dismissed and Oertl and his companions were prosecuted as heretics. They were sentenced to death but eventually pardoned and sent into permanent exile. Oertl settled in Protestant Nuremberg, where his brother-in-law was the well-respected copperplate engraver, illustrator, and publisher Johann Ambrosius Si(e)bmacher (1561-1612). Siebmacher was also the author of a highly acclaimed Wappenbuch (heraldic book). Siebmacher became the instigator, early collaborator and illustrator of Hieronymus Oertl’s multi-volume chronicle of the Hungarian wars against the Turks (1395-1607) as well as of the early editions of the Geistlicher Frauenzimmerspiegel. Unfortunately, no copies of these early editions seem to have survived.

The Hungarian wars and the Frauenzimmerspiegel were original compendia. Both began as chronicles, reformatting writings that were readily available in Augsburg and Nuremberg as centers of commerce as well as of the printing and illustrating trade. One can assume that the period of Hieronymus Oertl’s residence in Nuremberg, from 1580 to 1614 (ages 37 to 71), was the most productive of his career [2].

The first devotional book compiled by Hieronymus Oertl and illustrated by Johann Siebmacher was published in Nuremberg in 1610, just a few years before Oertl’s death in 1614. It was entitled Schoene Bildnus in Kupffer gestochen der erleuchten berumbtisten Weiber Altes, und Neues Testaments (Beautiful Portraits Engraved in Copper of the Illustrious and Most Famous Women from the Old and New Testament) and was dedicated to the Margravine Sophia of Ansbach, a pious patroness of Hieronymus Oertl. This book, it turns out, was not for sale. However, as devotional books grew in popularity, Margravine’s copy became the template for commercial editions that were published over the next century in various German, Dutch and Swiss cities. It should be noted that, unlike today, the designation Frauenzimmer had no derogatory meaning and was commonly used for ordinary women and occasionally with sweeping poetic license.

According to a recent count, twenty-three editions of the Geistlicher Frauenzimmerspiegel published between 1634 and 1755 are extant in various European and American libraries. The 1708 edition here is in a long duodecimo format, commonly used for small devotional books in the seventeenth century. In all editions, Hieronymus Oertl was acknowledged as the originator (inventor) of the book. However, others, such as clerics and poets, edited, enlarged, and embellished the text, even to the extent of being in competition with each other, sometimes to linguistically startling effects. An electronic edition of the 1755 Zurich edition of the Geistlicher Frauenzimmerspiegel (Zurich,1755) is available at the Niedersaechsische Staats-und-Universitaets-bibliothek in Goettingen. My family’s 1708 edition is therefore one of only a few survivors.

The engraved frontispiece tells us that this Geistlicher Frauen Zimer Spigel contains everyday prayers freshly composed by wise men and illustrated with copper plate engravings first used by Hieronimum Ortelium. According to the title page, this 1708 edition was to be the “last edition” offered for sale by the Hauensteinischer Buchladen in Hanover. A small engraving in the lower third of the page urges its readers graphically to strive for higher reward in paradise after death.

The title page gives the title as Frauenzimmer Spiegel and the author’s last name as Ortels. Below the title, the reader is encouraged to embrace the virtues practiced by illustrious (erlaucht) women (Frauenzimmer) of the Old and New Testament, presented here in beautiful stories (schoenen Geschichten), pious prayers (andaechtigen Gebeten) and uplifting sighs (aufsteigenden Herzensseufzern). Since Hieronymus Ortel and his two collaborators, the regional poet Johann Ritens and the Lutheran pastor Jacob Behmen (Boehme) had been dead for nearly a century, it is reasonable to assume that the 1708 edition was a reprint, though it would be worth actually comparing the text to early seventeenth century editions to confirm.

The text itself follows a familiar format. It contains uplifting stories (Betrachtung), prayers (Gebet/Gebaett), poetry (poetische Verse) and songs (Lieder) appropriate for almost every event in life such as birth, marriage, child rearing, illness, caring for the sick, death, widowhood and longing for the joys of paradise. Even recreational walks in the woods were to be undertaken with the proper praise for God’s bountiful creation. For our contemporary taste the language of these stories and prayers is extremely convoluted and flowery and it is difficult to properly capture the sentiments in contemporary English.

The neatly lettered handwritten personal dedication in the front of the book is particularly dear. It is most likely written in a nineteenth-century German script and appears to have been composed either by a bridegroom to his bride or by a husband to his wife and vividly echoes the sentiments that the Geistlicher Frauenzimmer-spiegel wanted to nurture. Here is the dedication as written in German—it has been transcribed and rendered in modern German orthography—and translated into English.

Widmung

Indem der Himmel Dich,

Jetzt mir, mein Schatz geschenkt,

Und unser beider Hertz,

Auf einen Schluss gelenkt,

So seh’ ich Dich nun

An als eine Gottesgabe

Die ich durch seinen Trieb

An Dir gefunden habe.

Nimm unterdessen dies

Zum Liebeszeichen hin

Und wisse dass Du mein

Und ich Dein eigen bin.

Was uns dies Buch verspricht,

Das wolle Gott Dir geben

Und was uns dieses lehrt

Nach solchem wirstu Leben

So bist Du mir mein Kindt

Hier eine Dorothee,

Ein Goettliches Geschenk

Und Labsal meiner Eh[r]

So werd ich dermals einst

Bei anderen Himmelsgaben

Dich wie allhier gescheh[e]n

An meiner Seite haben.

Dedication

In that heaven has presented me with the gift of you, my treasure, and our hearts have been guided in the same direction,

I now see you as a present from God that I found

because he directed it so.

Please take this [book] as a token of my love

and know that you are mine and I am yours.

What this book promises I hope God will grant you

and what this [book] teaches you shall live.

You are to me my child, like Dorothee,

a gift from God and balm for my honor

And so, with other heavenly gifts, I shall one day, as here on earth, find you by my side.

In the copperplate illustration introducing Eva, she does not seduce Adam with the traditional apple but sits in a primordial landscape gathering wool from the pelts of two minuscule lambs at her feet. She is dressed in a grass skirt and wavy hair down to her waist. Two naked male figures are barely visible in the distance. The characterization of Eva as a shepherdess is unusual in this context and not universally commended. In a review of the role of Eve as a shepherdess, the Athenaeum Journal (London, 1887) is unhesitatingly displeased and calls such a description “the crown of being characterless.”

The Journal would no doubt have been more pleased with the provocative Eva of 1755. The following excerpt asking for God’s blessing in the performance of daily tasks gives us insight into the general tone of the text.

“ … einem jeden seine Arbeit in seinem Stand und Beruf auferleget hast … Behüte uns auch dass wir unsern Zweck nicht in diese Welt setzen …”

“ … each one has been assigned his work in his calling or profession … protect us so that we do not seek our purpose in this world …”

The last verse of Eva’s text is a rhymed, heartfelt sigh (Reim- Seufftzer) and expresses the hope that the reader will one day be allowed to enjoy the pleasures of eternal life in paradise. The comparison of other copperplate illustrations from 1708 and 1755 show similar progressions.

Susanna, the Chaste, 1708 (left), appears rather shy about her nudity; half a century later in, 1755 (right), she is fully clothed and rather worldly looking.

Similarly, Maria Magdalen, the Repentant, is standing upright looking slightly bewildered in 1708 (left) dropping her jewelry, while she has fallen to her knees in 1755 (right) kissing Christ’s feet and asking for the forgiveness of her sins. The implied message here is one of submission to the mercy of the wronged husband through Christ’s grace. There are also copper plates that illustrate no particular biblical woman or virtue but highlight the ever-present grace and forgiveness of God.

For example, in 1708 (left), Die Ehebrecherin (adulteress) is fully covered in a black cloak visually suggesting that she silently repents her sin, while in 1755 (right) she is forced to confess her adultery to Christ in the company of other holy men, suggesting a male environment.

Perusing the Frauenzimmerspiegel raises many questions about gender roles assigned to men and women in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It also speaks to the public and private place of women in a patriarchal society at that time and how more enlightened thinking slowly began to redefine these roles into civic models.

I have donated my family’s Geistlicher Frauenzimmerspiegel of 1708 for safekeeping to the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries in honor of my maternal grandmother, Elisabeth Zimmer (1870-1949) and my mother, Maria Zimmer Esser (1909-1977), who lived enlightened lives.

———–

[1] The subject is best summarized by Ferdinand van Ingen, in “Frauentugend und Tugendexempel zum Frauenzimmerspiegel des Hieronymus Ortelius und Philipp von Zesens biblischen Frauenportraets” in: Barocker Lust-Spiegel, Studien zur Literatur des Barock (Amsterdam: Editions Rodopi, 1984) 349-383.

[2] Hieronymus Oertl is not the only Oertl family member mentioned in the chronicles of the time. Abraham Ortelius, the cartographer of King Philip II of Spain, is a contemporary of Hieronymus. Born in 1527 in Antwerp—his family migrated there from Augsburg in 1460—Abraham died there, a Catholic, in 1598. As the author of the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Antwerp, 1570), the first modern atlas, Abraham Ortelius is likely to have had contact with his Augsburg and Nuremberg relatives, since they would have crossed paths at the annual book and print fairs in Frankfurt and other marketplaces.

2 responses to “From Steamer Trunk to Rare Books Collection”

I’ve come across a number of reform siddurim (prayer books) targeted specifically at women from what was then called Breslau in the 1920’s. Do you think these books are a Jewish borrowing from the Geistlicher Frauenzimmer-spiegel or totally unrelated?

I would doubt a direct relation to the Geistlicher Frauenzimmerspiegel as plenty of prayer books and devotional books (Andachtsbücher) appeared since the early nineteen century addressing Jewish women (often using the term “Gebidelte Frauenzimmer mosaischer Religion”). Early editions were published in German and Hebrew Script, since the 1830 re-editions and new versions appeared mostly in German in script.

Without having seen the prayerbooks your are referring I would rather expect that they are related to these nineteen-century publications…