It’s a small but important collection, documenting the work of a local woman who lives in two worlds, those of art and business. She has managed to create an amazing collection of ceramic sculptures while also helping to run the family business (Parkway Corp.), begun by her parents, Herman and Lee Zuritsky. Moreover, a collection of over 500 photographs of performing artists, taken by her late husband Allen J. Winigrad, between 1973 and 1989, has been in the collection of the Penn Libraries since 1994.

Etta Zuritsky Winigrad is a Philadelphia artist and Penn graduate (FA’58 Ed’59) for whom ceramics have been her primary, though not her exclusive medium. Her thought-provoking sculptures, which combine figurative and fantastical elements, reflect her focus on the situation of humanity in the world. As she herself says:

From the very beginning, my sculptural work has been a continuing exploration and attempt to illustrate ideas and concerns of the human condition, both whimsical and serious.

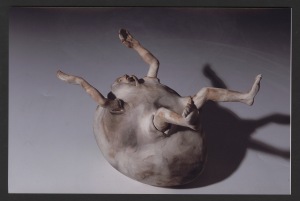

The figurative element in her work, as seen here in “Reborn,” provides a point of entry for the viewer.

By combining realistic and fantastical elements I am trying to encourage the audience to draw on their own imagination and life experiences for interpretation.

Over time, she developed a firing technique for her sculptures, which is fascinating, combining a conceptual framework with the serendipity of real life.

The recent sculptures are of a low fire white clay body that easily absorbs the smoke and carbon from the newspaper I burn around it out in the open after it has been fired to maturity in the kiln. The smoke acts as a paint brush which allows the color to appear as if created by the hand of nature and not as an applied coat of paint from the hand of man. By controlling the smoke, to some extent, I can use it to emphasize the forms and the way the audience views the piece.

Her influences are many, coming from the African, South Pacific, and pre-Columbian art that she and her husband collected, and which is on display in her home.

I especially like the simpler primitive shapes that speak to us so powerfully and seem to tap into those forms that we have genetically accumulated in our psyches.

Background

Etta (born July 25, 1936) recalls being six or seven years old when her parents, Herman and Lee Zuritsky, began their Philadelphia-based parking business. Etta recalls that even in her day, Etta’s mother Lee was active in the business. One of eleven children, Lee Zuritsky was the only one to finish high school, and Etta describes her mother as her role model and credits her for having the courage to pursue her dream.

In the late 1950s, when she went to Penn, she applied to the School of Fine Arts, rather than the College for Women, knowing that it was easier to get into the fine arts program, but that once you were in you could take any course at the University that you wanted. After graduating, she briefly taught junior high school before deciding that teaching was not for her.

She admits that up until the time she got married, she thought of art consisted exclusively of painting and drawing. After she was married and had her first two children, she would have a babysitter come in for a few hours and use her free time to go to the Philadelphia Museum of Art for classes in drawing and painting. One day the teacher gave them some clay and asked them to use the model to create a three-dimensional work. This was an epiphany for Etta, who discovered that what she couldn’t do with paint she could do with clay. However, everyone who works in clay begins by making pots, which Etta found to be limiting, so she began to look for whatever would teach her about sculpture. After that she looked for classes on sculpting with clay, even traveling out west to take them. Between 1968 and 1996, she took continuing education courses at Moore College of Art in Philadelphia, as well as workshops at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and other institutions across the nation.

Etta and Allen lived for years in Cherry Hill, NJ, raising their four boys (Michael, David, Jacob, and Daniel) there. It was there that she had her first kiln, built in a shed from bricks, where she did more traditional kinds of firing, like Raku. It was originally a gas kiln, but she converted it to electric so that she would have more control over the actual process of firing, since during the process of firing the temperature needs to rise and then lower gradually, so as not to crack the sculpture during the firing process. It was while living and working in Cherry Hill that she first developed the smoking technique that was to become one of her signatures.

When she moved to Paoli, PA, after her children were grown, she had a big studio with an indoor kiln, the largest one they made, allowing her to make much bigger sculptures. She smoked them after firing in the driveway. The studio in her current apartment (seen here) in Rittenhouse Square, to which she moved more recently, was designed to hold a smaller electric kiln, this one computerized to fire her work to her specifications without constant monitoring, since the firing process can take days. However, the final smoking process now takes place in the driveway of her son David’s house in Penn Valley.

Smoking technique

When asked how she came to the smoking technique that she uses to provide a patina to the surface of her sculptures, Etta says she probably came to it accidentally. She was looking for a way to unify the surface and move the eye around the sculpture without using traditional color. Color doesn’t speak to Etta the way it does to what she refers to as “real colorists.” Color draws you to a certain point, and she didn’t want viewers to focus on color, but on the whole piece. She didn’t want color to pull one away from the sculptural aspects of her work. And when she occasionally uses color, it’s intended for a specific purpose.

The success of this technique depends on both the type of clay she is using and the firing technique she employs. High-fire clays can be fired at high temperatures, which allow the clay to “vitrify,” that is, undergo a chemical change that drive out all the water molecules and makes the object waterproof. However, low-fire clays have open pores after firing, meaning they can absorb water and, in the case of Winigrad’s smoking technique, the carbon byproducts of combustion. Etta works with plain clays, generally white and gray, which work well as a receptive surface for tinting with smoke. The result is that it looks like the coloring has grown out of the piece rather than being applied to it.

She insists on using the Philadelphia Inquirer for her smoking, shying away from pages with color as well as the sport section. To “smoke” a sculpture, she wraps newspaper around the sculptures and carefully sets fire to it, manipulating it as it smokes. She uses wet paper to mask areas that she doesn’t want smoked. After smoking she sprays it with a fixative so that the carbon patina becomes a permanent part of the sculpture.

While Etta claims that the results of her smoking technique provide an element of serendipity to her work, her son David counters that she exerts more control than she admits, saying “I think the fire and smoke obey you.” On rare occasions she will employ color glazes, but only when she feels it is absolutely essential for the work. When she does employ color glazes, her color of choice is red and appears predominantly in sculptures which have a political or feminist leaning. The odd, full colored sculpture stands out in her collection for its appearance of a childlike whimsy.

Inspiration and Themes in Her Work

The inspiration for her work came in part from her travels abroad with her husband Allen, who was determined to see the world. Every year, at the end of the year, Allen, who was a dentist, would close his office and the young woman who worked for him would take care of the children while he and Etta went to India, China, Japan, and even Papua New Guinea, bring back the art of each of the cultures they visited. Etta’s apartment is filled with the fruits of their travels. A wall of masks from around the world greets you as your enter the apartment and another wall of masks fills the other side of the entry wall (seen here), serving as a focus for the living area. According to Winigrad, when we travel widely, like she did, we see things that take us out of our own western culture, we see different faces and the masks on her walls are like these faces. Her son David, an artist in his own right, who makes kinetic sculptures, also sees the influence of surrealism in her work.

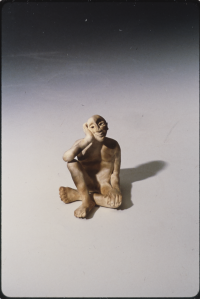

The primitive shapes used in her sculptures, like “Kiss, Kiss,” shown here, give the viewer an easy way to access the work. She encourages people to draw their own interpretations from the sculptures, and will never tell you if your interpretation is the “correct” way of viewing the sculpture.

In addition to these simple shapes, many of her works feature titles that have become clichés for daily life, making them more relatable to her audience. For example, her piece “Play/Life/Play”, a mixed media work, features a woman pushing a shopping cart in the foreground while children enjoy the garden and swings behind her.

Her figures tend to be male, like this one, part of a group called “8 Little Guys,” which she attributes to the fact that she only raised boys, so it made sense to “do boys,” as she says. Her figures have no hair and no clothes, so that they can speak to any male. They also serve as a counterpoint to the focus of male sculptors on nude female forms.

However, not everyone is able to appreciate the male forms for what they are. In 1993, Winigrad won an art contest organized by the Central Bucks Chamber of Commerce. The title of her sculpture was “Blue Boy” and featured a nude male without a head or arms and with a gaping hole for a stomach, but the rest of his body was anatomically correct. The sculpture was put on display at a Bucks County Bank for a few days before the manager removed it from the lobby and placed cardboard over its genitals, claiming that the sculpture was too graphic for the bank’s clientele.

Birds and trees also appear in many of her sculptures. Birds “represent me, as an observer … not actively involved, but watching, keeping an eye on things” while trees “speak to me.” They are “singular in the way they grow, like humanity.” The sculptures reflect “on what I see in the world I live.”

While she now works predominantly in clay, several of her pieces contain elements of both painting and sculpture. These pieces tend to be softer and more whimsical than her clay works, perhaps due to the saturation of color. Her sculptures intended to be hung on walls also possess a two-dimensional feeling. Their lines and curves are less dramatic and the sculptures themselves are more figurative than fantastical, demonstrating her mastery over many mediums.

She works from sketches, like this one for “The Dictator,” seen here with the finished sculpture and while she has a general idea of what the finished piece will look like, she may make changes as she moves from two dimensions to three. While she starts with an idea, she may finish with a different one, has the final work “has to speak to me artistically.”

When asked about a favorite sculpture, she claims to have no favorites. Once she finishes a piece, it’s done, despite all its flaws and imperfections, since she has said “what I wanted to say.” Winigrad says that what gives her greatest satisfaction is when someone responds to her work. In her view, people acquire her works because they see something they recognize, something that speaks to them. She only uses the human figure because it helps lead people into her work and connect with it.

The rest of the apartment is filled with art as well, pottery and other three dimensional works they collected on their travels, interspersed with Etta’s sculptures and Allen’s photographs and furniture.

When asked about a highlight of her artistic career, Winigrad immediately responds that it was being invited to have the archive of her work, including photographs and information about each of her sculptures, at the Penn Libraries, where other people can access it.

Winigrad is nationally renowned and her work is in many public as well as private collections. This past July she once again exhibited some of her work at the Muse Gallery in Philadelphia.

SELECTED EXHIBITIONS

JURIED EXHIBITIONS

- Arts Guild New Jersy, Rahway, NJ – 2012

- Old City Jewish Arts Center, Philadelphia, PA – 2011

- Regional Center for Women in the Arts, West Chester, PA – 2009

- Target Gallery, Alexandria, VA – 2008

- West Chester University, West Chester, PA – 2008

- Hunterdon Art Museum, Clinton, NJ – 2008, 2011

- Visual Arts Center of New Jersey, Summit, NJ – 2006

- Cheltenham Art Center, Cheltenham, PA – 2006

- New Hope Arts Center, New Hope, PA – 2005, 2007, 2008, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014

- Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX – 2005

- Philadelphia Sculptors, Philadelphia, PA – 2005, 2006, 2008

- Community Arts Center, Wallingford, PA – 2004

- Lancaster Museum of Art, Lancaster, PA – 2003

- Guilford Handcraft Center, Guilford, CA – 2003

- The Clay Studio, Philadelphia, PA – 2000, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2007, 2011

- Cambridge Art Assn. Cambridge, MA – 1999

- National Ceramic Competition, Florence, AL – 1999

- Grounds for Sculpture, Hamilton, NJ – 1998

- New Jersey Center for the Visual Arts, NJ – 1997

- Artspace, New Haven, CT – 1997

- Washington Square Sculpture Show, Washington D.C. – 1997

- State Museum of Pennsylvania, Harrisburg, PA – 1996, 1997, 2000, 2006

- Wayne Art Center, Wayne, PA – 1992, 1993, 1995, 1997, 1999, 2000, 2004, 2006, 2007, 2008

- Mainline Art Center, Haverford, PA – 1995, 1997, 2005, 2007, 2008, 2012, 2014, 2016

- Art Association of Harrisburg, Harrisburg, PA – 1995

- Central PA Festival of the Arts, State College, PA – 1994, 1995

- Annual Bucks County Sculpture Show, Doylestown, PA – 1994, 1995

- National Ceramic Competition, San Angelo Museum of Art, TX – 1993, 1995

- Creative Arts Workshop Center, New Haven CT – 1995

- Abington Art Center, Jenkintown, PA – 1992, 1993, 1994

- Pavilion Gallery, Mt. Holly, NJ – 1992, 1994

- Owen Patrick Gallery, Philadelphia, PA – 1994

- Stedman Gallery, Rutgers University, Camden, NJ – 1991, 2010

- National Museum of Ceramic Art, Baltimore, MD – 1991

- Baltimore Clayworks, Baltimore, MD – 1990

- Museum of American Jewish History, Philadelphia, PA – 1981, 1983

- Philadelphia Art Alliance, Philadelphia, PA – 1979, 1983, 1998

INVITED EXHIBITIONS

- Delaware County Community College, Media, PA – 2004, 2010

- National Liberty Museum, Philadelphia, PA – 2004

- Hartwick College, Oneonta, NY – 2001

- Clay Studio, Philadelphia, PA – 2000

- Bucks County Community College, PA – 2000

- Langman Gallery, Willow Grove, PA – 1999

- Riley Hawk Galleries, Columbus, OH, curated by Gail Brown – 1999

- “Exploring a Movement – Feminist Visions in Clay”

- St. Mary’s College, Los Angeles, CA – 1995

COMMISSIONS

- “Early Rider”- J. Blank Collection, New York, NY – 1997

- Winner – Holocaust Memorial Competition -1981

- Jewish Federation of Central New Jersey

- Collection of Holocaust Center, Kean College, New Jersey

PUBLICATIONS

- Ceramics Monthly “Singularities”, Feb. 2001

- Ceramics Monthly “Upfront” 1996, 1998

- Sculpting Clay by Leon Nigrosh 1992

AWARDS

- Art Association of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

- Pennsylvania Festival of the Arts, State College, Pennsylvania

- Main Line Art Center, Pennsylvania

- Abington Art Center, Jenkintown, Pennsylvania

- Pavilion Gallery, Memorial Hospital, Mt. Holly, New Jersey

REPRESENTATIONS AND AFFILIATIONS

- Muse Gallery, Philadelphia, PA – 2017 show

- Qbix Gallery, Philadelphia, PA – 2005 show

- Gloria Kennedy Gallery, Brooklyn, NY – 2007, 2008 shows

- Figurative Gallery, La Quinta, CA – 2004 show

- Artists’ House Gallery, Philadelphia, PA – show 2004

- Miller Gallery, New York, NY – 2000 show

- Artforms Gallery Manayunk, Philadelphia, PA – 1999 show

- Gallery 500, Elkins Park, PA

- ArtSites Gallery, Greenpoint, Long Island, NY