[Ed. note: Today’s post is by Penn Libraries intern Akasya Benge. Many thanks to Akasya for her painstaking work in inventorying recently acquired Japanese Naval Collection magazines (Kaigun, Kaigun Gurafu, Umi to Sora, and Teikoku Kaigun) and reflecting on what she found within. Come check the magazines out for yourself in Van Pelt-Dietrich Library Center!]

I came to the University of Pennsylvania Libraries as an intern with already specialized interests. I studied abroad in Japan in high school, college, and post-graduate, and obtained my master’s degree in art history with a focus on premodern Japanese art. However, the project I ended up focusing on at the Penn Libraries was to inventory a sizable collection of 1930s and 1940s Japanese naval magazines. These magazines provide a look into propaganda both prewar and while at war, allowing readers to explore a subject little known or researched in the West – the presentation of upcoming war to the Japanese public.

It seems an odd choice for any university outside Japan, but the University of Pennsylvania Libraries has one of the largest collections of pre-WWII Japanese naval material in the United States, primarily dating from the 1920s-1940s. Indeed, it is the rarity of these materials that makes them so fascinating. While the United States understands its own narrative and choices leading up to and the conclusion of World War II, less is known in the Western world about how the Japanese people felt during those same troubled times, especially because of their own efforts to whitewash their imperial past after the war.

The focus of this post is the Japanese naval and aviation magazines held by the Penn Libraries, readily available publications to the Japanese reading public of the time. They have such names as Umi to Sora 海と空, a title that translates to “Sea and Sky,” and expresses an equally evocative image in Japanese as it does in English. The early 1930s publications of this magazine are scattered with meticulous diagrams of airplanes, as well as peaceful hovering planes gently soaring above the sea.

Beautifully detailed drawings of ships – which seem more suited to a children’s book than a military magazine – are also contained in these issues. A sense of hope pervades the pictures, the feeling that much had been accomplished and so much more awaited. Foreign militaries are approached with a feeling of inquisitiveness and interest, rather than malice and fear. This would quickly change with the 1940s, where Americans became distant and unapproachable, and the Germans, interestingly carefree and friendly. There is even a photograph of Hitler printed in the magazine Kaigun Gurafu 海軍グラフ in 1938, both commanding and terrifying; this image provides a stark contrast to the photograph published four years earlier of the Shōwa Emperor (known as Hirohito outside Japan) looking gentle and shy.

Other changes that occur over time in Sora to Umi include minute details such as the use of Japanese years rather than the Western calendar, in Chinese numerals: for example, Shōwa 17 昭和十七 as opposed to 1942. Something so barely perceptible may not seem of interest, but as linguists know, a strict demand to use only Japanese words and eliminate all traces of foreign influence marks a time of nationalism, and possibly gave fuel to the upcoming war.

In Kaigun Gurafu 海軍グラフ (Navy Illustrated), meanwhile, in the middle of 1938 we can observe another subtle change. From the glossy, graphic-design heavy magazines produced earlier, we temporarily receive something reminiscent of the Edo period (1603-1868): heavy, striped paper with feather-like sheets inside reminiscent of Japanese rice paper or washi 和紙. The cover, instead of the usual dramatic photograph, is emblazoned with a simple stamp, reminiscent of woodblock prints. This image from May 1938 shows the rising sun, along with a ship and airplane intersecting the top and bottom.

The changes to the cover and the return to a traditional Japanese calendar illustrate the ways in which the Japanese are proclaiming their native heritage. In the 1930s and 40s, Japan was an expanding empire steeped in patriotic media, and there was a strong effort to establish the Japanese emperor’s identity as a living god with roots stretching back into the mists of time. This is amply on display here, with the image of the rising sun literally being reinforced with new displays of power – by air and sea.

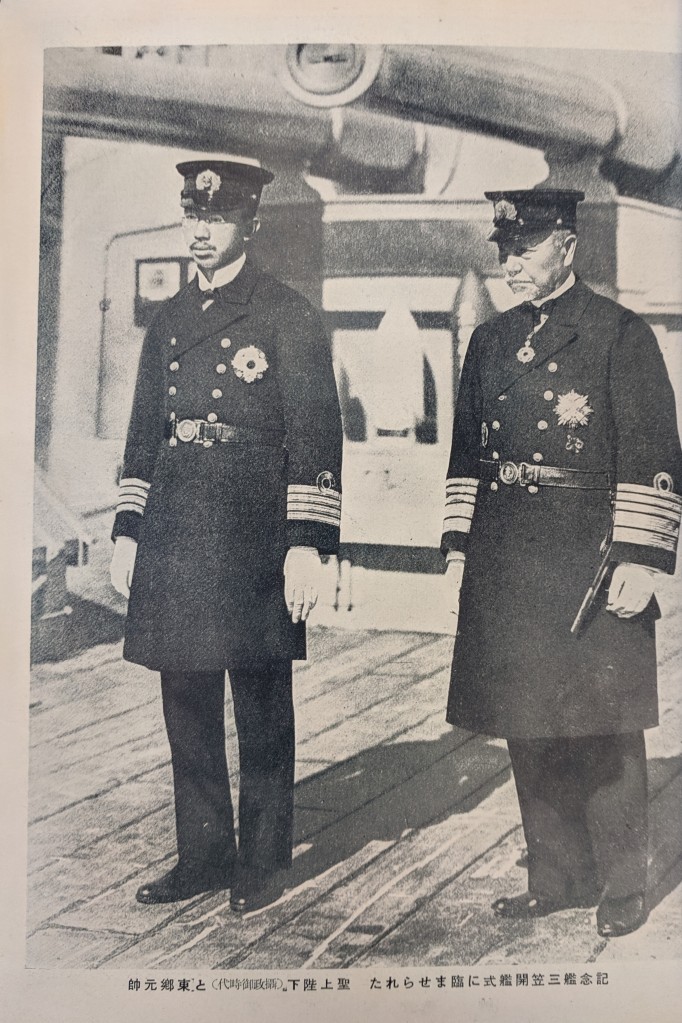

Kaigun Gurafu relies less on imagery and more on facts than Sora to Umi. (Although, as its name implies — “gurafu” is short for “photograph,” indicating an illustrated publication — it always contained sections of glossy photos of various naval scenes.) However, even this publication inserts a loving tribute to Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō 東郷平八郎 (1848-1934), who began his naval career during the Meiji period (1868-1912) as a dapper and handsome young man, and even appeared on the cover of Time Magazine on November 8, 1926. Upon his death in 1934, multiple Western nations sent representative dignitaries to his funeral.

Another interesting aspect of Kaigun Gurafu is the advertisements. The advertisement on the very first page of many mid-1930s issues show a woman proudly displaying her new household gadgets, ranging from everything from a fan to a vacuum.

Upon first glance, Western readers may think of a husband indulging his wife in state-of-the-art appliances, but the truth is this may not be the case. Japan has long had a system of women managing household finances, and it seems likely that this practice began in the 1930s, when the financial and industrial conglomerates known as zaibatsu 財閥 kept the economy relatively healthy despite the Great Depression ravishing the rest of the world. “Salaryman” サラリーマン (a term that originated in the 1930s) in Japan traditionally turned over their monthly salary to their wives and in return received pocket money or okozukai 小遣い to cover their monthly expenses like food, shopping, and entertainment.

So, in a magazine that we might assume had targeted men, why were items meant for women being advertised? It is possible that women were buying the magazine. Given that even European and American women’s reading habits are not well studied, how much less is known about the reading habits of Japanese women in the 1930s? Even more illuminating are our own attitudes to early Japan, where many assume was repressive for Japanese women. By the Shōwa era, were women as enthusiastic about the military as men? Did they read these magazine in earnest for their sons or themselves?

Regardless, by 1938, the advertisements directed towards women were moved from the front to the back, and the clothing they wore (modern, Western, and freeing) was replaced with traditional kimono. Now a woman, instead of actively cleaning, sits demurely in front of a Mitsubishi space heater, practicing her calligraphy.

Another advertisement shows two women, painted as old-fashioned beauties, both in kimono, using a Mitsubishi sewing machine to then make even more kimono. The message is clear: we don’t want your Western ideas (or products) here.

For me, to study such a different era than the one I normally focused on gave me an opportunity to see the artwork and ideology comparison from one era to a much earlier one. What remained quintessentially Japanese both at war and at peace? I hope it will encourage other researchers to dive further into this unknown tract of research, and bring to light more perspective that is not our own.