Author: Marissa Nicosia

-

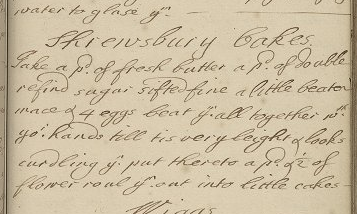

Shrewsbury Cakes

[Ed. Note: Today’s post is part of Alyssa Connell and Marissa Nicosia’s “Cooking in the Archives” project, which launched in June 2014 with support from a UPenn GAPSA-Provost Fellowship for Interdisciplinary Innovation. Alyssa and Marissa are transcribing, adapting, and cooking recipes from Penn’s collection of manuscript recipe books. Visit their site to learn more about…

-

In the Rare Book Room with ENGL 234

This post was written in collaboration with the students in my course, ENGL 234: Social Networks from Shakespeare to Facebook: Topics in History of the Book. Since we were all aware that seeing, examining, and handling early printed works by Shakespeare and his contemporaries might be a once in a lifetime opportunity, and is certainly…

-

Cheap and Common

This post is a collaboration between Adam G. Hooks (U. of Iowa) and Marissa Nicosia (UPenn) — and is cross-posted at Adam’s blog anchora and the Penn Libraries’ blog Unique at Penn. This started as another post in Adam’s “Breaking Apart” series, which has recently focused on leaf books (see here, here, and here). As…

-

Poems from UPenn Ms. Codex 1552: Before and After Manuscript

I first encountered Ms. Codex 1552, Vade mecum, at a meeting of the English Paleography Workshop. A group of Penn librarians, graduate students, and faculty; scholars and graduate students from other institutions; area librarians, book-dealers, and other interested parties joined Amey Hutchins in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library on the sixth floor of Van…